2022 Party Over its Out of Time – Does Andy Warhol’s Illustration of Prince Infringe Lynn Goldsmith’s 1981 Copyrighted Photo?

A Case of You – What Brought this About?

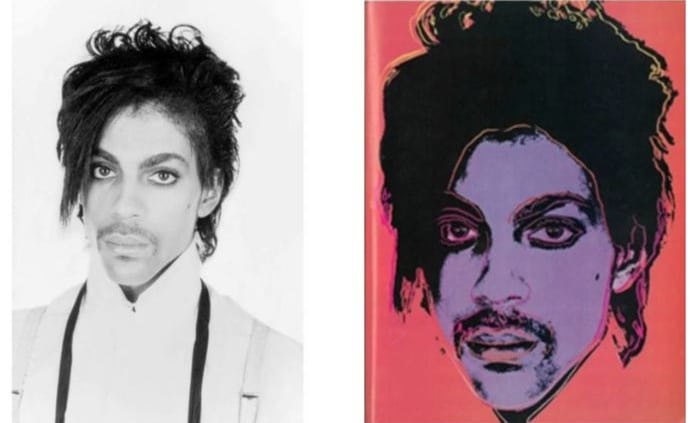

In 1984, artist Andy Warhol created a series of silkscreen prints and pencil illustrations depicting the musician Prince (Warhol’s illustration is shown above on the right). Warhol’s prints and illustrations were based on a photograph of Prince that was taken by photographer Lynn Goldsmith in 1981 in which she holds copyright (Goldsmith’s photo is shown above on the left). Goldsmith licensed the photograph to Vanity Fair magazine for use as an artist reference. Unbeknownst to Goldsmith, that artist was Warhol. Also unbeknownst to Goldsmith (and remaining unknown to her until 2016), Warhol did not stop with the image that Vanity Fair had commissioned him to create, but created an additional fifteen works, which together became known as the Prince Series.

The Question of U – What is Fair Use?

Copyright protection extends both to the original creative work itself and to derivative works, which it defines as, in relevant part, “a work based upon one or more preexisting works, such as a[n] . . . art reproduction, abridgement, condensation, or any other form in which a work may be recast, transformed, or adapted.”

The fair use doctrine seeks to strike a balance between an artist’s intellectual property rights to the fruits of his/her own creative labor and the ability of others to express themselves by reference to the original work. The statute provides a nonexclusive list of four factors that courts are to consider when evaluating whether the use of a copyrighted work is “fair use.” These factors are:

(1) the purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes;

(2) the nature of the copyrighted work;

(3) the amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole; and

(4) the effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work.

The fair use determination is an open ended and context-sensitive inquiry, “not to be simplified with bright-line rules[.] . . . All [four statutory factors] are to be explored, and the results weighed together, in light of the purposes of copyright.”

Controversy -Transformative Work or Derivative Work?

While a determination of whether “fair use” exempts a work from infringement, this post, and the case involving the Prince Series, focuses primarily on the first factor – the purpose and character of the use. This factor requires consideration of the extent to which the secondary work is “transformative” or “derivative” in nature. In making this determination, one must consider “whether the new work merely supersedes the objects of the original creation, or instead adds something new, with a further purpose or different character, altering the first with new expression, meaning, or message.” The intent of the artist to create something of a different nature or character is not controlling. Rather, one must consider how the secondary work may “reasonably be perceived” in relation to the original work.

Congress, in defining “fair use” in the Copyright Act, specifically recognized certain uses as being transformative. Criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching, scholarship, and research are all considered by statute to be “transformative” and thus not an infringement. The Supreme Court has further recognized parody as transformative in that it “needs to mimic an original to make its point”. In each of these situations, it is quite easy to see how the secondary work serves a manifestly different purpose from the original work itself.

The “transformative uses” listed in the statute are not exclusive. Courts have determined many secondary works to be transformative that do not fall into these enumerated categories. For example, in another case similar to this one, a court considered secondary works that incorporated, among other materials, various black-and-white photographs of Rastafarians

from the primary work. In determining that at least some of the secondary works were transformative, the court observed that the secondary artist had incorporated the primary photographer’s “serene and deliberately composed portraits and landscape

photographs” into his own “crude and jarring works . . . [that] incorporate[d] color, feature[d] distorted human and other forms and settings, and measure[d] between ten and nearly a hundred times the size of the photographs.”

On the other hand, lets consider a film adaptation of a novel. Such adaptations commonly add a significant amount to their source material: characters are combined, eliminated, or created out of thin air; plot elements are simplified or eliminated; or new scenes are added to name a few. These modifications are further filtered through the creative contributions of the screenwriter, director, cast, camera crew, set designers, cinematographers, editors, sound engineers, and myriad other individuals integral to the creation of a film. Courts have long recognized that “[w]hen a novel is converted to a film . . . [t]he invention of the original author combines with the cinematographic interpretive skills of the filmmaker to produce something that neither could have produced independently.” Despite the extent to which the resulting movie may transform the aesthetic and message of the underlying literary work, film adaptations are almost universally considered to be derivative works rather than transformative. For instance, even though one familiar with his work can readily recognize the Godfather films as a product of Francis Ford Coppola, they nonetheless are still too closely based on the novel by Mario Puzo to be considered transformative.

Nothing Compares 2 U – Goldsmith’s Photo compared to Warhol’s Illustrations

One can see that in the case of the Prince Series, there is no clear cut answer. Warhol’s secondary work cannot reasonably be perceived as commentary, criticism, parody, or any of the other recognized uses that are routinely considered transformative. On the one hand, Goldsmith argues that the pose in which Prince is depicted in her photo bears a number of striking similarities to the pose in Wahol’s illustration – the angle, expression, even Prince’s hair style are “substantially similar”. Goldsmith further argues that in copying these aspects of her photo into his illustration, Warhol has failed to transform the meaning or message of the work into something different from the original. Goldsmith concludes that the Warhol illustration shared the same purpose as her photograph and retained its essential artistic elements, and therefore is not transformative.

Warhol, on the other hand, points to the removal of certain elements from the Goldsmith Photograph, such as depth and contrast, and embellishing the flattened images with “loud, unnatural colors” as transformative in portraying Prince as an “iconic” figure rather than the “vulnerable human being” depicted in Goldsmith’s photograph. While these changes clearly turn the work into something that is readily recognized as a work by Warhol, the appeals court considered this to be akin to the adaptation of a novel into a film. Just as Coppola’s adaptation of Puzo’s The Godfather was not transformative, even though it is readily recognized as a Coppola film, the court concluded that Warhol’s adaptation of Goldsmith’s photo was not transformative.

Sign O’ The Times – SCOTUS to make final decision

On March 25, 2022, the U.S. Supreme Court agreed to review the appellate court’s finding that the Worhol painting was not transformative. The Court could either side with the lower court finding that the Worhol work was transformative, or affirm the appeals court finding that it was not. In any event, the Court will almost certainly give some additional guidance on how to apply the fair use test to determine when such works do, or do not, qualify as a transformative use that does not infringe. The Court isn’t expected to hear the case until the fall term commences in October, so a decision won’t be made until probably sometime in early 2023. Stay tuned and we will provide updates when the case is heard and decided. In the meantime, if you have issues or concerns regarding copyright infringement, contact us – we would be happy to help you!